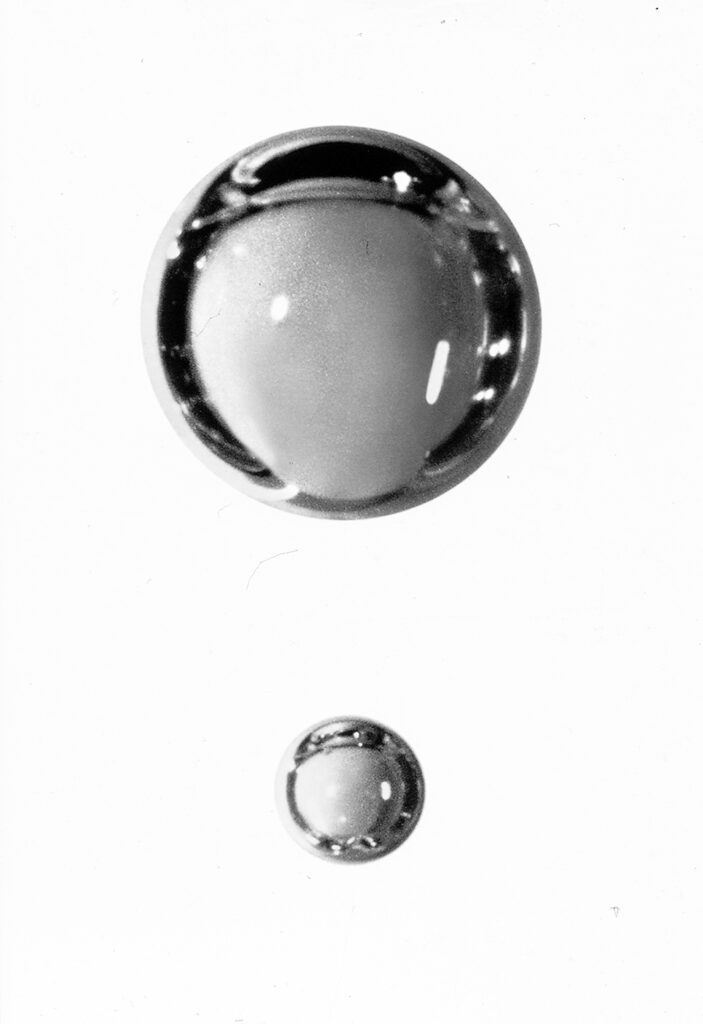

The Beautiful Bubble

ART & SCIENCE

Gérard Liger-Belair is France’s—if not the world’s—most renown researcher in the phenomena of effervescence. Professor of chemical physics at Reims University in Champagne, he is the author of more than one hundred scientific and technical articles. How does a bubble go, and why, and where? And what if we…

Liger-Belair is also an aesthete. A lover of a speaking, beautiful image.

This series of black and white photographs from 1999 is his first love; it launched not only a career but also an intellectual obsession. Taken with film then scanned years later, these images represent the raw vision of an experimental young photographer, an art form at its best and the pure, formal beauty of nature.

Interview with Professor Gérard Liger-Belair, below.

extracts from a discussion with Gérard Liger-Belair

Some, but not all, scientists have an aesthetic appreciation for their subject of study.

I need beautiful things so that I have desire to work on them. It’s essential. My motor for this scientific work was, in the beginning, an aesthetic one.

Are these images the first in your career?

This collection is unique to me. It’s associated with the pleasure of working in a dark room, developing them, doing the prints myself. I did everything. Many all-nighters. I don’t have the patience to do silver nitrate photography today. I use excellent digital cameras, but I cannot capture the same beauty as back then.

How did you start photographing bubbles?

I was always fascinated by sparkling drinks, and very quickly interested in photography. Between the ages of 15 and 20, I photographed insects using macros lenses, a flash, and much patience. I transferred these techniques to photographing bubbles, and that is how it all started. I had no idea what the result was going to be but I felt there was something interesting to follow in the movement of a bubble in a glass.

How did this turn into a course of scientific study?

I sensed that things did not happen at random, and that aesthetic and scientific research could be combined. I sent a thesis proposition to Moët & Chandon to see if they were interested in working on my thesis together and they were—they asked me to come to Epernay. It was the opportunity of a lifetime. And now, 25 years later, I’m still working on the same subject though I must do research that produces results and for industrial purposes. I do a lot less on the aesthetic side as I did back then.

Is there a moment in the trajectory, in the life of a bubble, that particularly fascinates you?

What captivated me back then was the trajectory of the bubble when it is alone; we see a separation between bubbles obeying scientific law and a mathematical progression. We can almost feel it.

A few years later, I got access to a rapid camera which allowed me to visualize something I couldn’t see before: the explosion of the bubble on the surface. The moment the bubble breaks is absolutely incredible. The bubble projects at high speed and breaks into little drops—very graphic. It’s not photography, really, it’s like high-speed film.

The beauty of science.

I began to love science when I started to understand an extraordinary structure made by nature; we want to understand these laws that make something so beautiful. This understanding has always driven me further.

Uncorked: The Science of Champagne, Princeton University Press, 2004

Un Monde de Bulles, Ellipses, 2020

Champagne: La Vie Secrète des Bulles, Cherche Midi 2014

Voyage au Cœur d’une Bulle de Champagne, Odile Jacob, 2011

Les Vins Effervescents: du Terroir à la Bulles, Dunod, 2008